If all the ammonia plants used to produce agrochemical fertilizer were immediately shut down, a third of the world’s population would starve. Half the nitrogen molecules in our bodies have passed through a Haber-Bosch reactor. Industry now extracts as much nitrogen from the air as all natural bacterial processes on Earth combined. These staggering statistics on ammonia synthesis have been compiled by geographers such as Vaclav Smil and chemical historians like Jens Soentgen. It would be difficult to cite a chemical process with more troubling implications. It affects us more closely than we realize, and its reach is far greater than we might imagine.

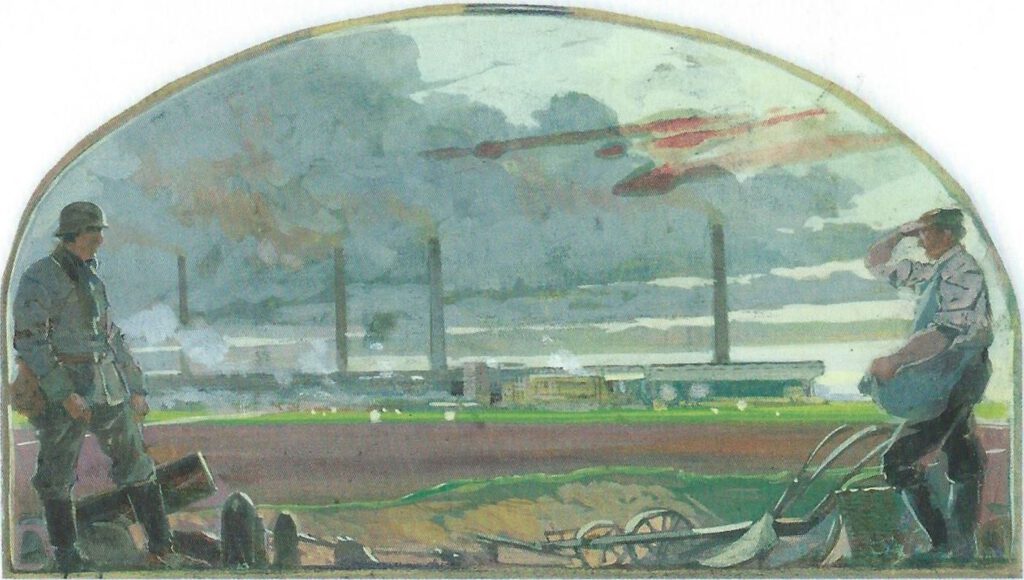

The high-pressure synthesis of ammonia (NH3), in which a catalyst – usually a compound of iron (Fe), aluminum (Al) and potassium (K) – binds nitrogen (N) and hydrogen (H), was developed by BASF before the First World War. This process has since become one of the most problematical monuments to twentieth-century science and industry. The artificial molecules it generates, and the processes they drive, are omnipresent – not just in all ecosystems and human bodies, but at every level of twentieth-century history itself. The Haber-Bosch process is tied to not only global nutrition but also destruction on a global scale and vice versa. Even before they were used to manufacture artificial fertilizer, the first ammonia factories in Ludwigshafen and later Leuna supplied ammunition for the First World War. The production facilities built for this war of attrition were then repurposed for agriculture. ‘Bread and death from the air’ was coined to cover the ambivalence in the 1920s.

Industrial fertilizer production can be linked to large-scale and planetary contexts in two ways. The construction of its infrastructure requires planetary networks, processes and strategic considerations. And in turn, planetary networks, processes and strategic considerations arise from its products.

The technical process, the individuals involved, and the great wheels of world history which ammonia synthesis immediately set in motion after its development have been the subject of countless accounts – from academic histories of science and geography to sensationalist industrial novels printed in the hundreds of thou-sands, which from the 1930s to the 1950s mythologized German chemists. The story has all the hallmarks of a classic technological drama: ‘ingenious inventors’ such as Carl Bosch, tragic figures” like Fritz Haber – whose wife Clara Immerwahr shot herself with his service revolver as he refined chemical warfare – a world war and the ‘solution to world hunger’.

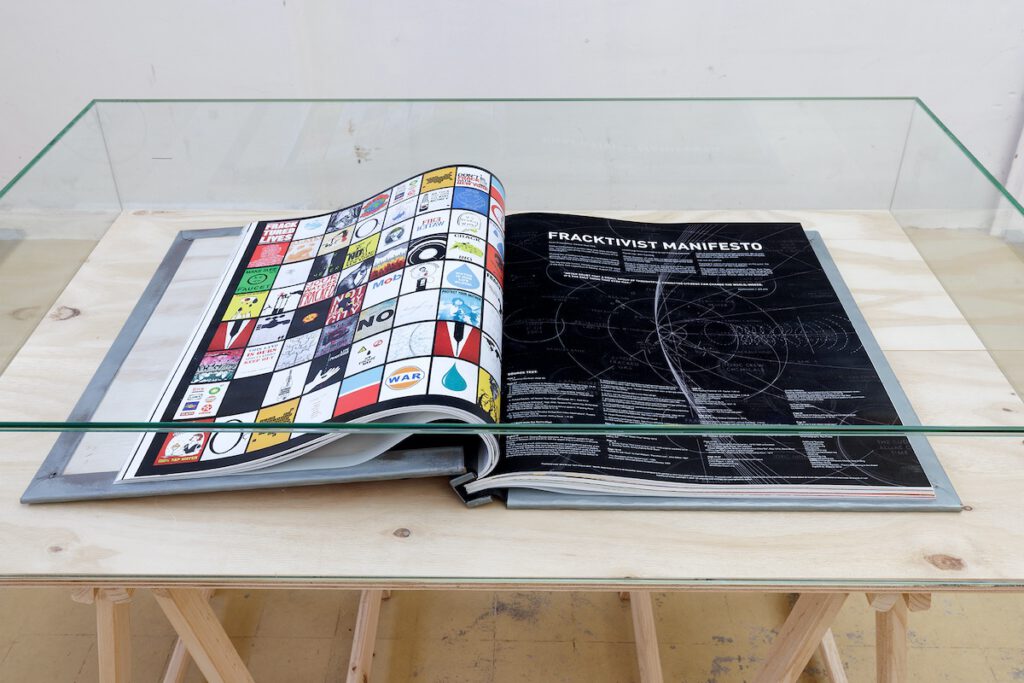

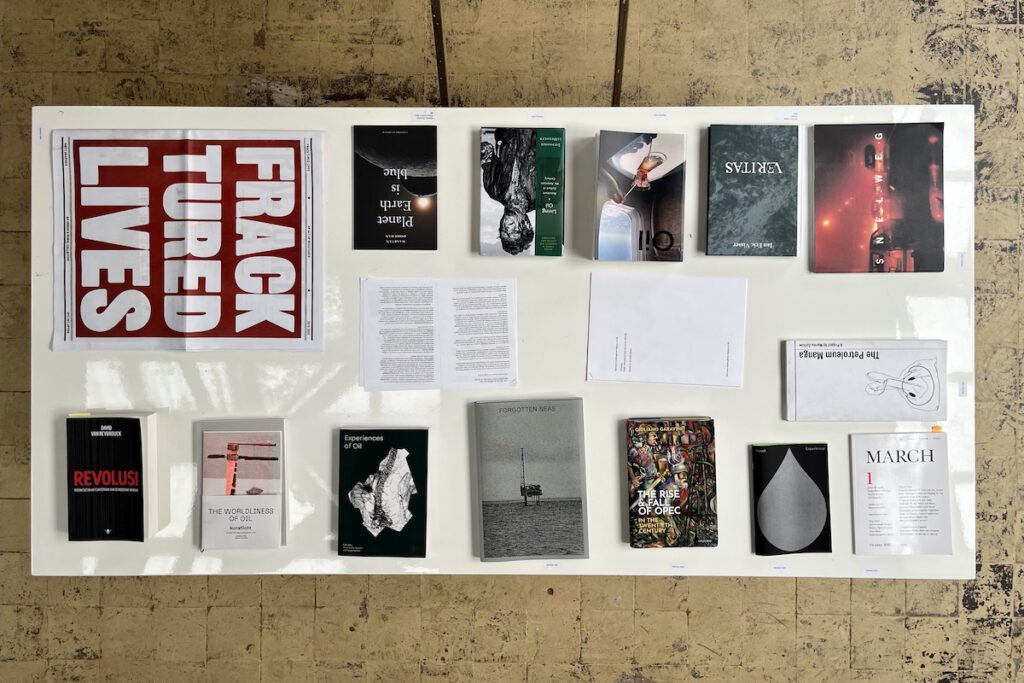

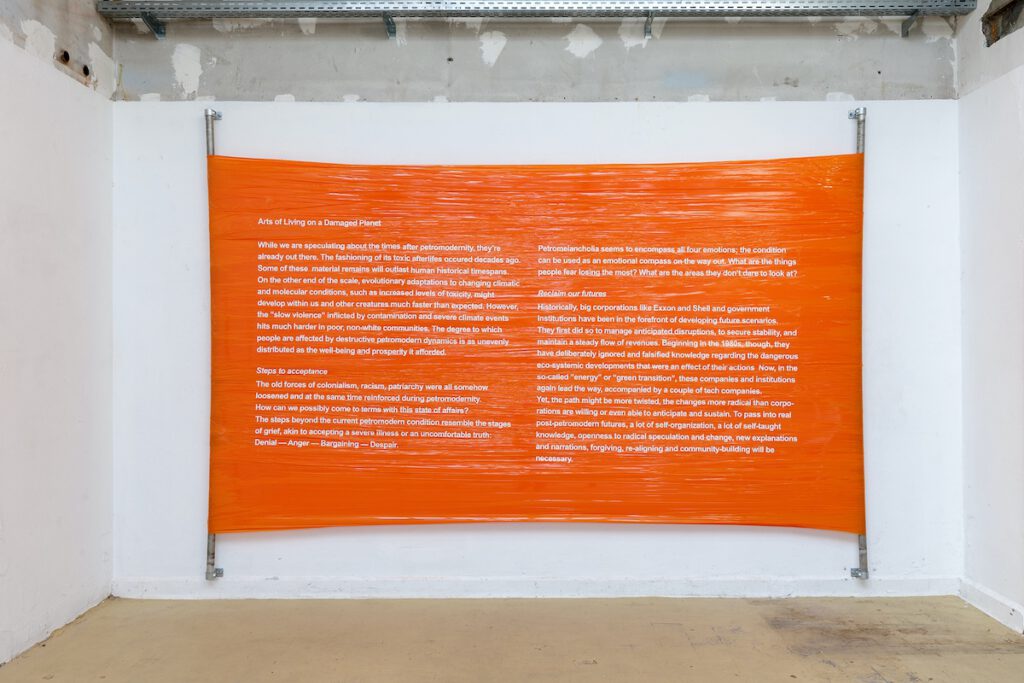

Yet the familiar narrative requires rethinking. The setting, the framework and the dilemma have shifted in recent decades. With the emergence of the Anthropocene and the realization that human-industrial activity is transforming Earth’s systems and natural history in the long term, ammonia synthesis also appears in a new light. Regarded for nearly a century as a technological triumph that alleviated global crises, it is now a planetary crisis in itself. Even as its destructive potential was acknowledged – most recently in the 2020 Beirut explosion, when an ammonium nitrate storage facility blew up – its role as an existential problem remained largely overlooked.

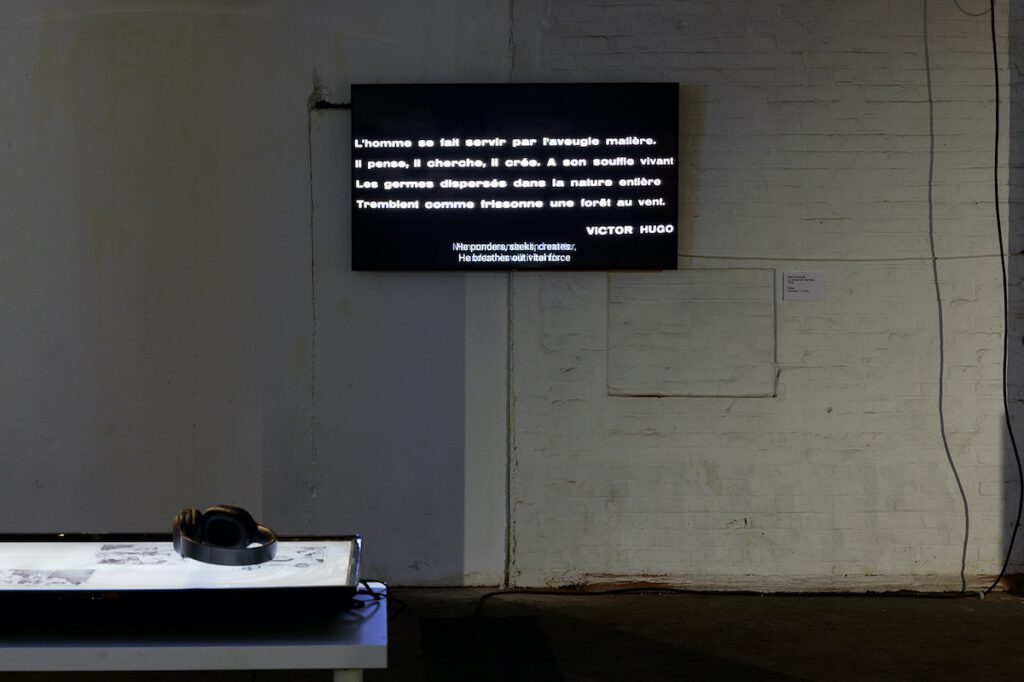

Almost all the hockey stick graphs mapping the Great Acceleration of Earth system and sociocultural parameters in the second half of the twentieth century – CO, emissions, biodiversity loss, erosion, ocean acidification, resource depletion – are directly linked to the global production of artificial fertilizers. The Green Revolution reshaped agriculture, fuelling population explosion, urbanization, and the transformation of entire eco-systems. Artificial molecules don’t merely shape world history for nations and humans (as was already evident around 1914); they also inscribe themselves into Earth’s history, affecting all other forms of life. And they do so in ways that deviate from their original intended purpose.

At the upper end of time scales that are only abstractly comprehensible to humans – at the level of the natural history of the future – previously unforeseeable processes must now be factored into the overall picture of ammonia synthesis’s effects. This, in turn, calls for a reassessment of all other scales embedded in the broader process. Artificially fertilized agriculture is planetary agriculture; the chemical industry of artificial fertilizers is a planetary chemical industry. The significance – and destructiveness – of this technology lies in its partly intentional, partly unintentional entanglement of vastly different scales, processes and systems.

Ammonia synthesis became a paradigmatic case for the concept of ‘planetary technology’, a term used by cultural and epistemological theorists since the 1920s. Under the impact of the attrition of the First World War, which was itself driven by this technology, writers such as Ernst Jünger, Walter Benjamin and Martin Heidegger explored the deeply ambivalent nature of a technoscience that not only endowed humanity with planetary power, yet also subjected it to ‘gigantic’ structures no longer within its control.

A century later, ammonia synthesis presents multiple, highly specific manifestations of the ‘planetary’ and the ‘technical. Its history is one of extremes. The Year Without a Summer in 1816, when volcanic ash from Mount Tambora’s eruption the previous year in Indonesia triggered global famines, inspired Justus von Liebig to establish the foundations of agricultural chemistry, recognizing the need for a precise understanding of the chemical requirements of plants and soils. Agriculture, he observed, depends on the continuous supply of phosphorus, potash and nitrate (i.e, nitrogen compounds). The depletion of soils had been understood since antiquity, yet solutions remained elusive, whether in Mesopotamia, Italy or North Africa. Soils that remain stable over long periods in their natural state depend on specific geological and climatic factors. In the Nile Valley, their fertility relies on the continental influx of mineral and organic silt from the tropics, while in the fertile loess plains and black earth regions in Ukraine and the American Midwest, they are sustained by fossil forest soils transported across continents by glaciers.

In the nineteenth century, global trade networks were established to supply German fields with nitrates unavailable in Europe, sourced from Chile or the guano islands of the Southern Hemisphere – a dependency that proved disastrous during wartime naval blockades but became surmountable once the atmosphere itself, above all the nitrogen it contains, was harnessed as a chemical resource. But according to Haber-Bosch, nitrogen could only be converted into ammonia at a pressure of 300 atmospheres and at high temperatures close to the point where iron begins to glow red-hot. Even then, a catalyst was required to accelerate the reaction. In Haber’s early experiments, this was osmium – one of the hardest, rarest and most expensive metals in the Earth’s crust. However, due to its extreme scarcity with the global supply at the time amounting to a mere 40 kilo-grams, it was entirely unsuitable for industrial-scale operations.

To conserve this limited stock, artificial metal compounds were developed and tested in 6,000 experiments conducted up until 1912 in search of a viable alternative. This led to a cascade of technical hybrids: food through plants through fertilizer through nitrogen through an iron-based catalyst enhanced with aluminium and potassium compounds, which is still in use to this day. Yet, despite the advent of electron microscopy and femtosecond lasers (1 fs = 0.000,000,000,000,001 sec) in the 198os, as well as Al-driven advances in physics and chemistry, its precise function on an atomic scale remains incompletely understood.

Thanks to its factories in Ludwigshafen-Oppau opened in 1913 and the Leuna works built in just nine months near Merseburg in 1917, Germany was able to fight the First World War – but also to lose it, as the Treaty of Versailles transferred its patents to the victorious powers. The petrochemical industry – driving the production of plastics, high-performance fuels and solvents – was built on an almost identical infrastructure through transatlantic collaboration between German coal chemistry and American petrochemistry, spearheaded by I.G. Farben and Standard Oil.

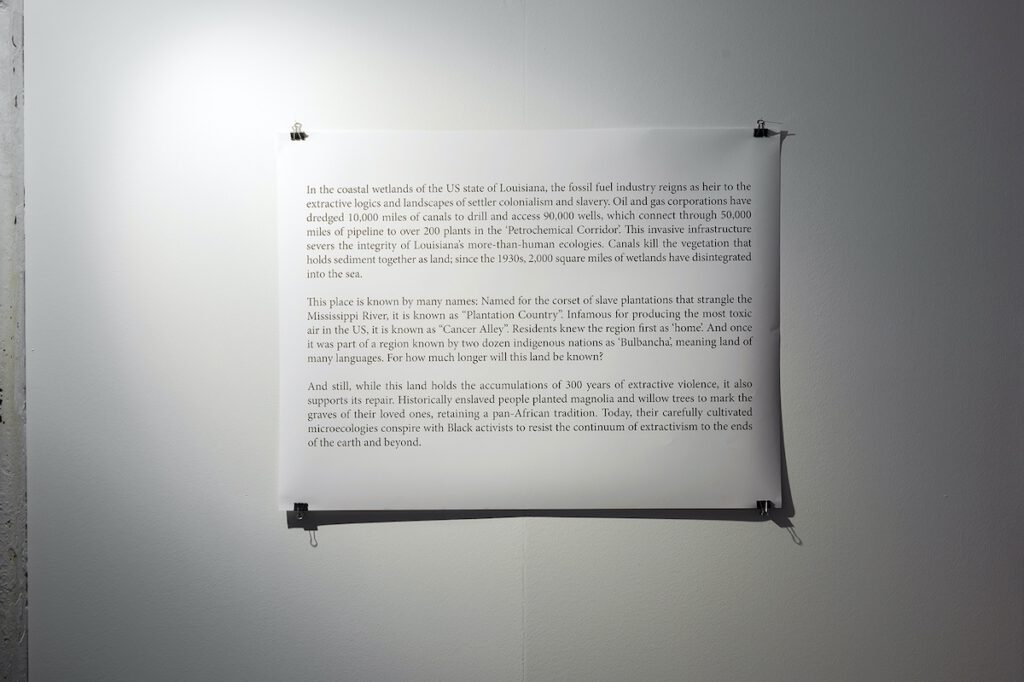

By the time of the postwar Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle), ammonia synthesis had merged with petrochemistry: the hydrogen needed to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen no longer came from water but from cheap natural gas. Today, the process spans the globe – from China, the Volga and the Caribbean to Louisiana and the Persian Gulf – acting as a planetary reactor fusing atmospheric nitrogen with lithospheric hydrogen in order to feed it into the biosphere. However, nearly 70 per cent of the nitrates applied to fields don’t end up in crops, animals or on dinner plates. Instead, they leach into rivers and oceans, fuelling explosive algal blooms and creating oxygen-depleted dead zones from the Baltic Sea to the Gulf of Mexico.

Resolving the contradictions between growth and destruction – between what began as a kind of ‘liberation’ from age-old agricultural constraints during the Green Revolution and today’s critical, once again tightly constrained predicament, in which every scale, from the nitrogen molecule to the entire biosphere, is entangled – will take time, if it ever succeeds at all. The first step is to recognize, articulate and expose the contradictions. They are laid out before us, undeniable and immediate.

Consider this: within the EU, consumers can reliably expect food labels to disclose the presence of potential allergens such as celery or peanuts. Yet, in stark contrast, there is no equivalent labelling for the Anthropocene imprint on our plates – no indication of the chemical-biotic synthesis behind the ingredients we consume, a synthesis shaped by processes spanning all geohistorical layers, systemic spheres, and both quantitative and qualitative planetary scales.