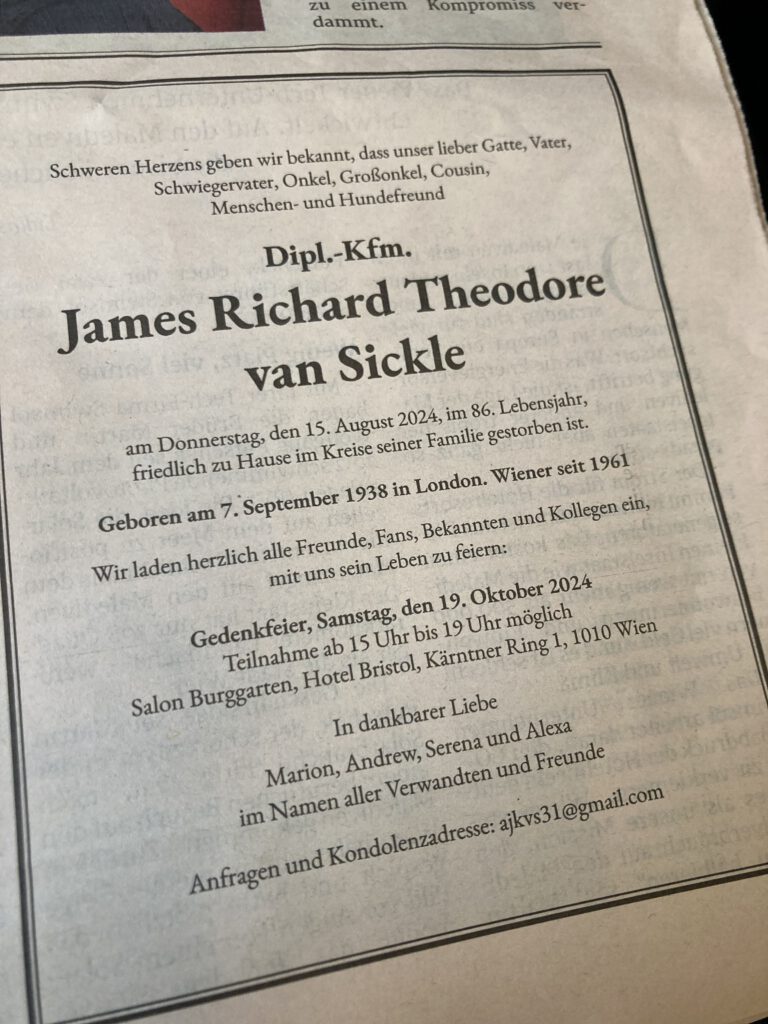

James van Sickle was a generous friend of our project since in 2013 he opened his family archives to our work, those of a Scottish-Huguenot Canadian-Galician-Romanian-Austrian oilman. In 2022, he became the only private sponsor of the translation of our German language ‘Atlas of Petromodernity’ into his English mother tongue—putting the name of van Sickle alongside those of the Goethe- and a Max Planck Institutes. In fact, at least three essays in our book (‘Pumpjack’, ‘Adventurers’, ‘Animals in Oil Fields’), have a direct relation to him and his archive. We were happy to send him the news that the book was finally published this summer, though he could not see the result any more.

James van Sickle was born in London in 1938. He lived in Vienna, Austria since 1961. Until he sold the company in the 1990s to OMV AG (Österreichische Mineralölverwaltung AG), he was head of what was founded as ‘Tiefbohrunternehmen Richard Keith van Sickle’ in 1937 by his father Richard Keith (1899-1961) and handed over to James in the early 1970s after an agonizingly long inheritance dispute.

James was the descendent of one of the families of adventurers who followed the global routes of oil in the late nineteenth century. Through his mother Dorothea Alice Cooke-Yarborough he also had an aristocratic background. To explain to his children “why we are nomads” he wrote a family chronicle that stretches from Sudan, Canada, the Middle East, and Austria. His grandfather and uncle had started drilling on oil in Petrolia, Ontario in the nineteenth century, then as many Canadian specialists from that place—called ‘hard oilers’—went to Galicia in the Habsburg Empire (now Ukraine), and further to Australia and Romania.

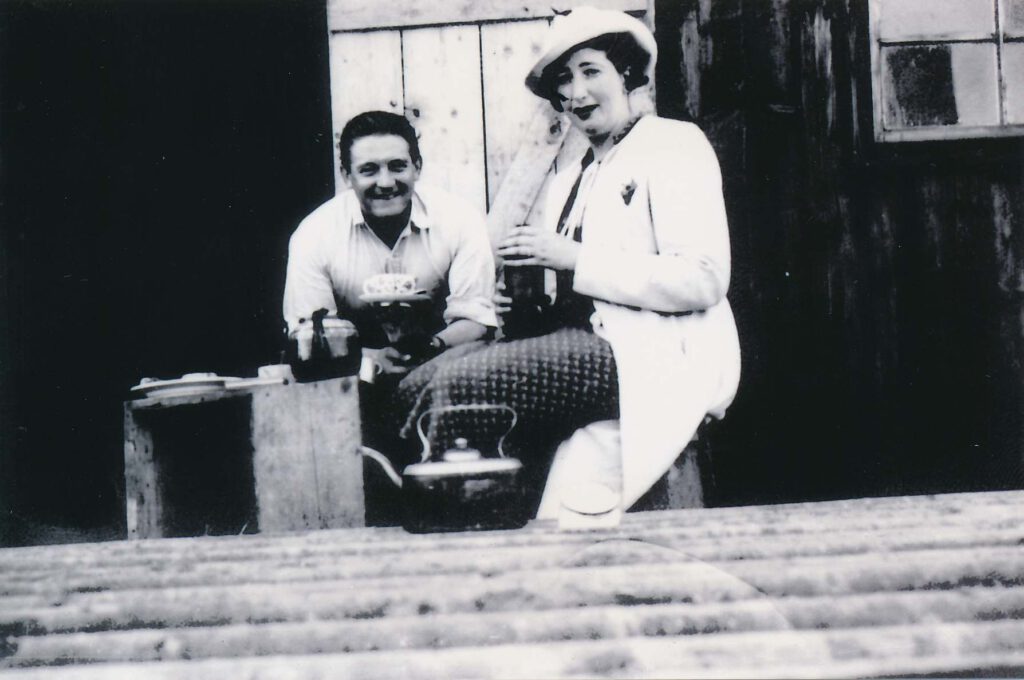

There, in Câmpina, James’ father, Richard Keith van Sickle, was born in 1899. His story connects family and world history in the most intimate way which made it the subject of our ‘Adventurer’ essay in the atlas. And since it was James who brought all this to us, by his archival material, hís chronicle, and his detailed explainings, is seems right to retell his father’s story in our orbituary to him. Keith van Sickle studied mechanical engineering in Cambridge and after working in oilfields in Romania in the 1920s, he turned towards Austria. For some years he owned a small castle and manor at Marbach in Upper Austria, at a place that by coincidence later lay some hundred meters away from the Mauthausen concentration camp. In the mid-1930s, he acquired mining claims at Neusield/Zaya at the Vienna Bassin. As early as 1937 van Sickle was forced to cede part to Deutsche Petroleum AG. It was here where, after the Anschluss—the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938—that on behalf of Deutsche Petroleum AG, van Sickle drilled the most productive oil well in the territory of Greater Germany at St Ulrich, Neusiedl/Zaya. On Kodak color amateur footage from 1939 we see Reichsstatthalter Arthur Seyss-Inquart walking by at the festivities to open the well, and then van Sickle. While a dual power of attorney, granted to his lover Elfriede Krasa and trustee Hermann Fritsche, took care of business during wartime, van Sickle himself was to be found on the other side of the front, fighting against an army fuelled by this oil. He trained as a pilot in the First World War, and from 1939 onwards, he served as a major in the British Royal Engineers Corps in North Africa, and later as lieutenant colonel and oil-attaché in Baghdad and Tehran. Meanwhile, in London, the German Luftwaffe was laying waste to his wife Dorothea’s mansion in genteel Sumner Place Nr. 2, once used to mortgage Austrian mining claims. In 1945, van Sickle returned to Vienna via Indonesia. His oil fields had suffered thoroughly through brutal German war exploitation and they sat in the Soviet zone. But van Sickle was used to dealing with Soviets from his time in Tehran, and decided to stand up to them. Based on a Russian tip, he acquired a magnificent mansion in Baden near Vienna, and was named in the Staatsvertrag, the treaty which guaranteed Austria’s independence in 1955. He died in 1961 from bladder cancer, and Elfriede Krasa fought desperately to not let James get hold of the company.

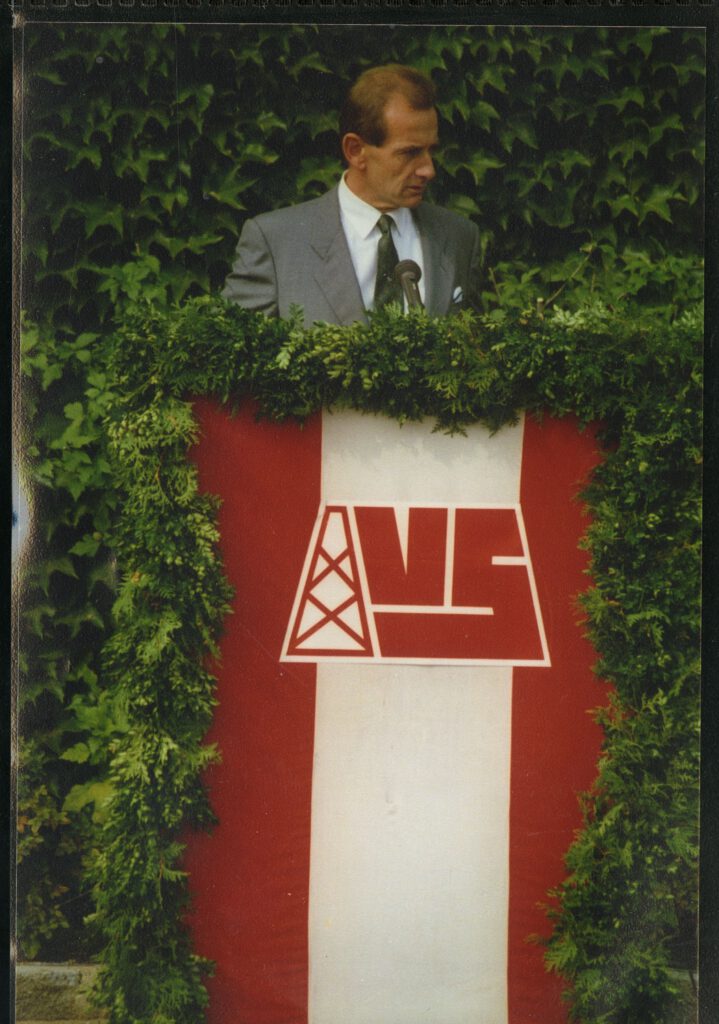

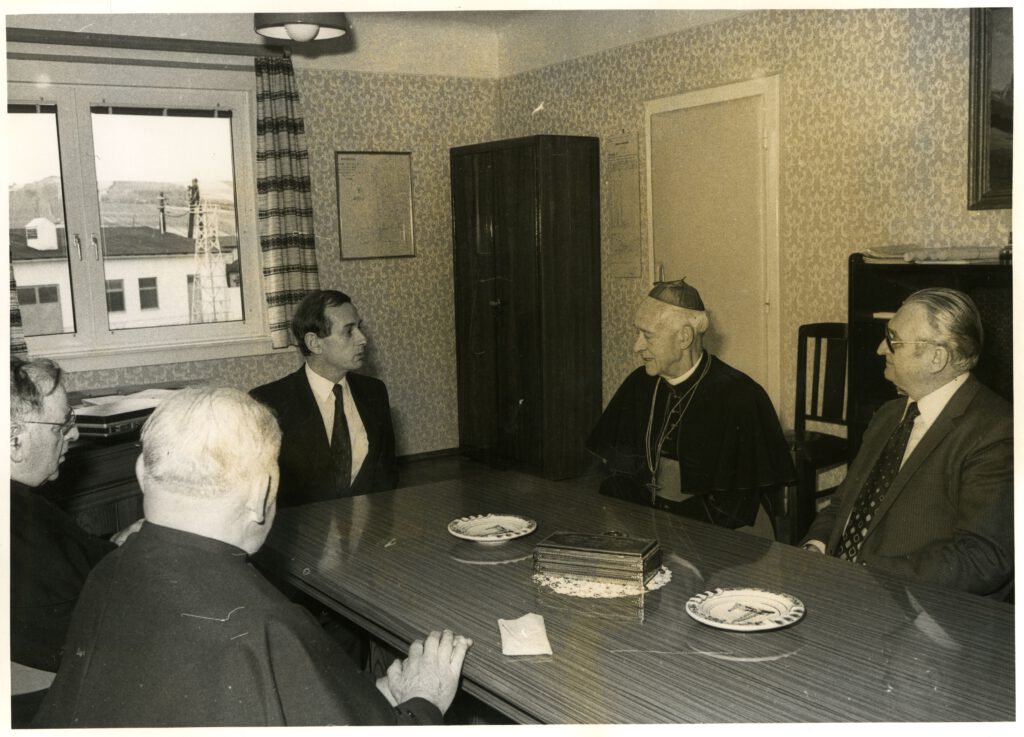

After a long decade of missed investment into the old infrastructure James van Sickle could restart with his team in early 1970s. Photo albums show the life of both the company and family at Neusiedl, and the challenges to operate with old and outdated machinery. A refinery and laboratory that was put into place to also profit from downstream added value was managed not at least by help of Marion, James’ wife who was trained as a chemist. And we see long trains with his logo shipping van Sickle oil and products into the world. But productivity was difficult to keep, and in the 1990s James sold the company, the wells and infrastructure to OMV. His former employees still kept the spirit of a certain independence. When we started in 2012 with Rohstoff-Geschichte to access unofficial documentations of the Austrian oil industry we could integrate a lot of photographs and even films from proud van Sickle workers into our digital collection and in one case later into our atlas.

It was during this project, in 2013, when James van Sickle kindly opened his private archives to our research. More than a thousand documents such as letters, photographs, a drilling diary from Romania 1925, and some unique amateur film footage from the oil fields from the 1930s were digitized and put into the archives of the Geological Survey of Austria (GBA, now GeoSphere Austria).

In long meetings at the lobby of Hotel Bristol in Vienna or at his home at one of the most beautiful places of Vienna in the middle of vineyards, we got to know James van Sickle as a subtle and witty storyteller—in his distinguished Austrian German with just a slight and genteel British accent. We learned about his racing cars (a Lotus Eleven) in his “playboy years”, about leading a company in 70s and 80s Austria, about war times between London, Vienna, and Neusiedl—about global oil history in the twentieth Century through the intimate looking glass of a family history—that in this unique case we luckily were offered by James.

We express our deep condolences to his wife and three children, and we hope to keep James van Sickle’s and his family’s memory alive through our work.