Presentation by Alexander Klose at Petrocultures 2022 conference in Stavanger.

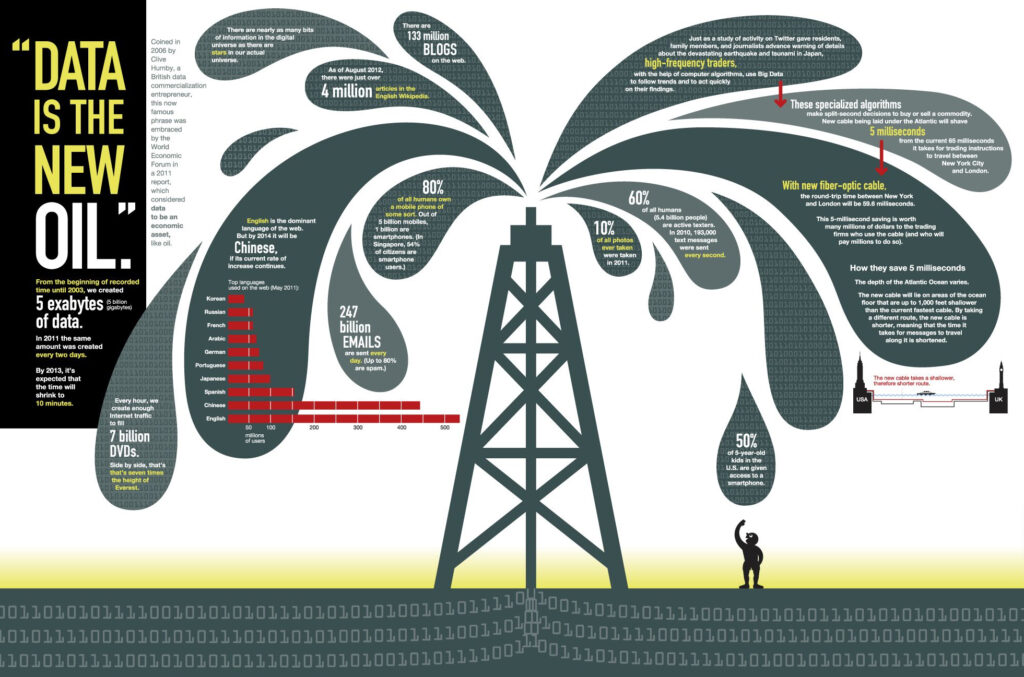

The talk tracks the relationship between the „digital age“ and petromodernity. As much as data is called the new oil today, oil has been the new data from the 1950s onwards. There may even be a homology of how these technologies tackle with and bring forward new realities, if you compare cracking–as the core petrochemical operation in which the molecules of hydrocarbon substances are torn apart and their atoms are recombined in new molecular compounds–with the way digital computers symbolize and re-organize material realities. Today, the worlds of social media and gaming are mostly keeping the petromodern promises for individual empowerment and entertainment. Fossil capitalism’s logic of extractivism has been extended both to new raw materials that are needed for the lightweight technology and to the consumers whose behavioral traces have become the “new oil”. What are the chances, what are the dangers of a media and energy transition „beyond oil“ that prolongates petromodernity?

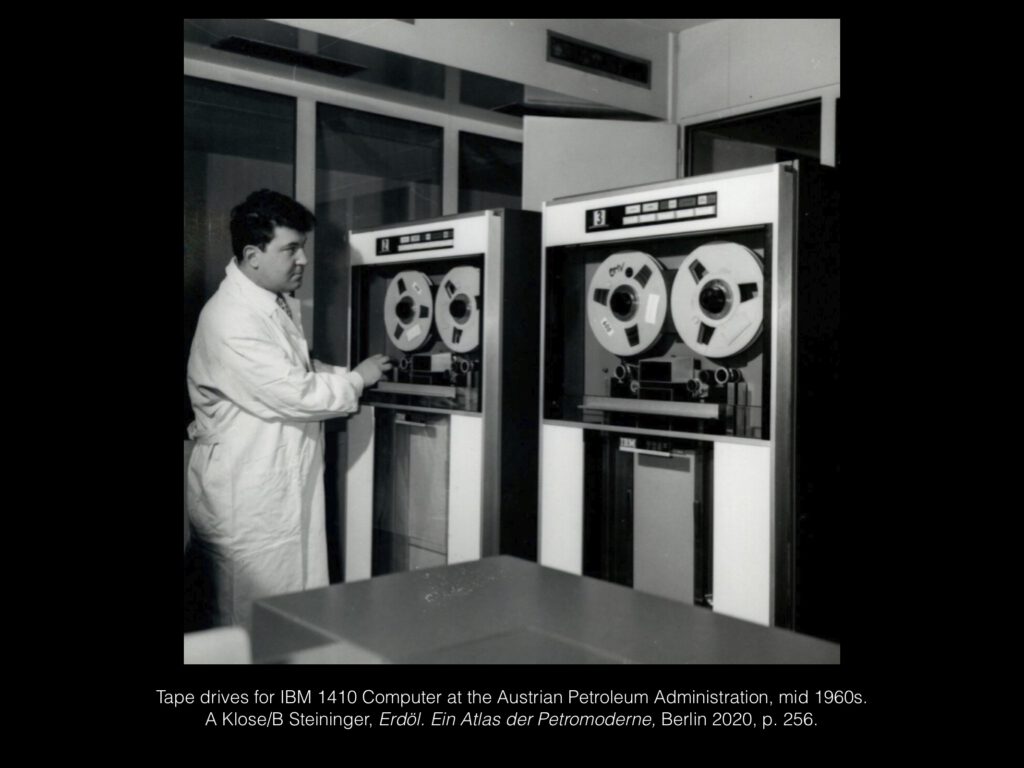

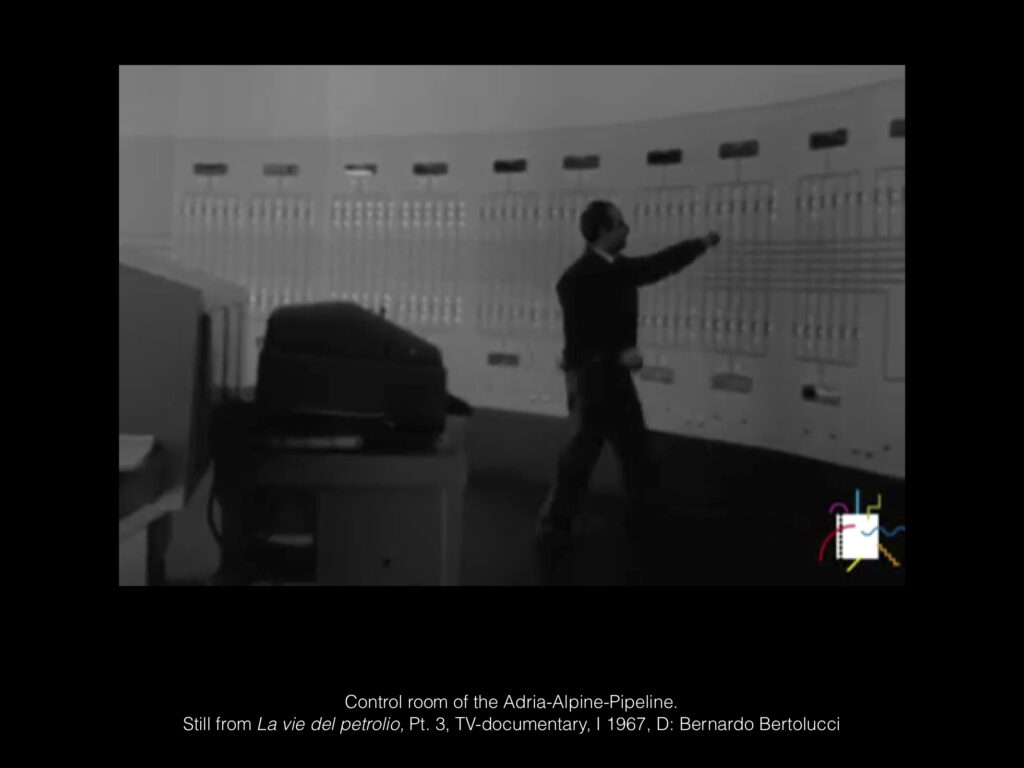

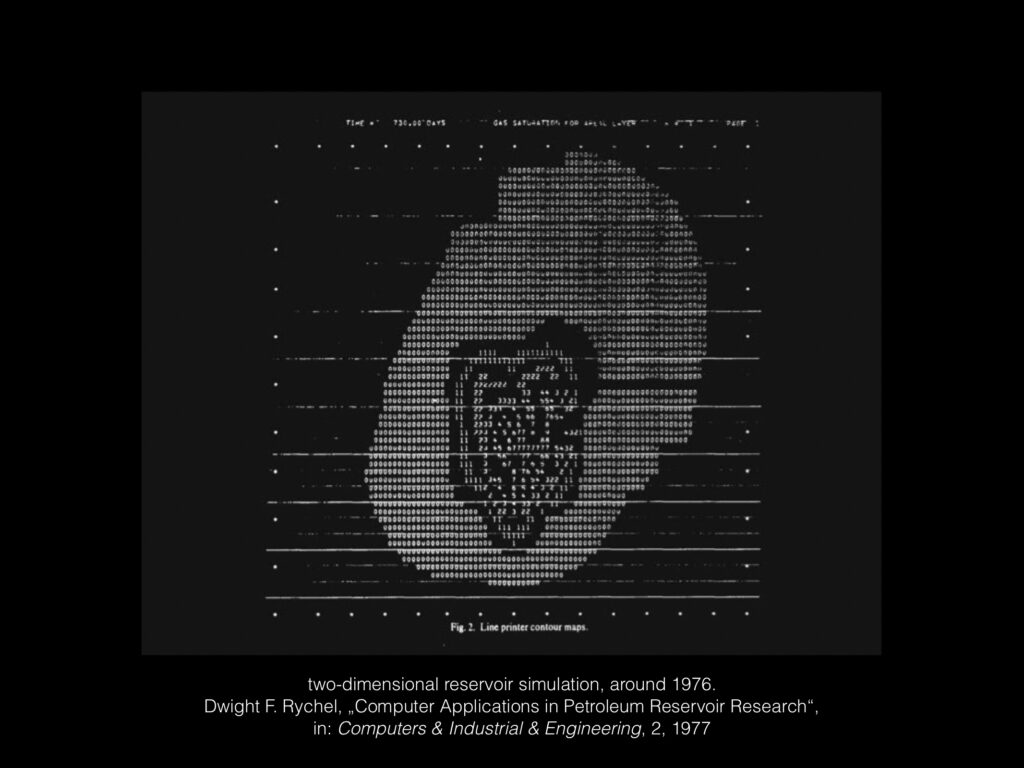

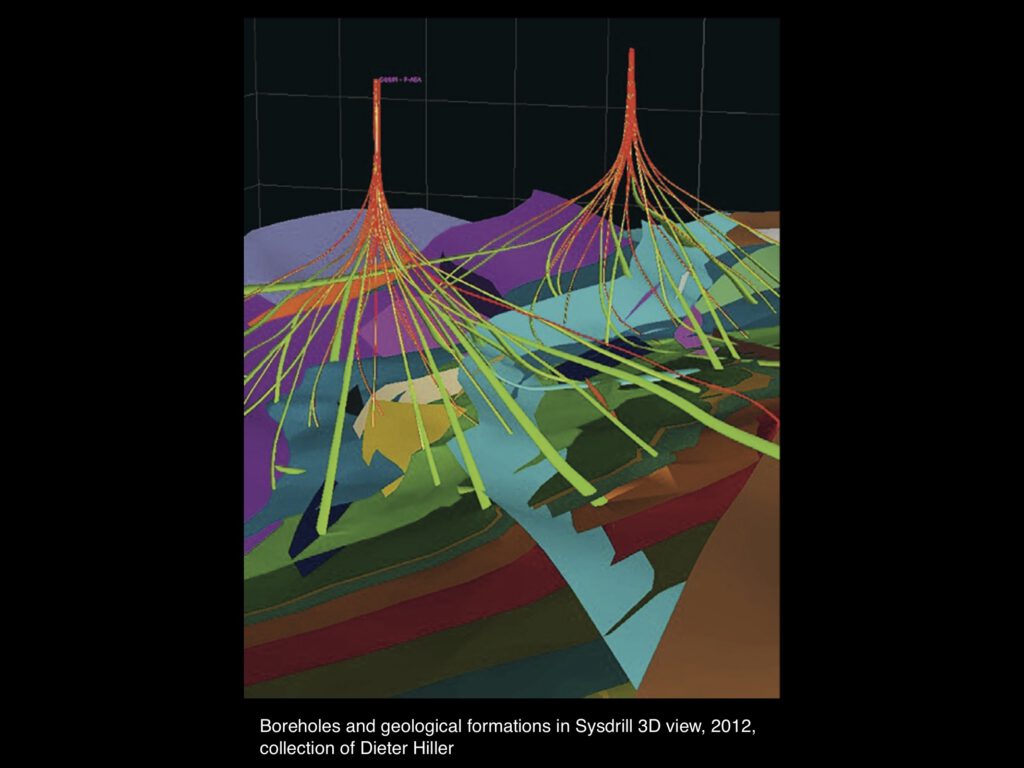

IT and industrial technology have never been separated as the story of a new digital age seems to imply. Quite the opposite, the oil industry has been one of the most important drivers of digital technology development from early on, namely for oil exploration.

The mining and development of “tough oil” reservoirs would not have been possible without computers. As much as data is called the new oil today, oil has been the new data from the 1950s onwards.

Action in the digital sphere happens in „the cloud“ – a metaphor that evokes lightweight molecules and accumulations in thin air. As we all know, the truth looks distinctly different: the global digital technosphere is made of millions of kilometers of cables and megatons of concrete, plastics, steel and silicium.

If the internet were a country, it would range third in electricity consumption after the U.S. and China. (Research Group Digitization and Social-Ecological Transformation, Berlin 2019.)

Even if the new very large data centers run on renewable energy, the carbon footprint of digital technology as a whole has become frighteningly significant.

While the use of these devices differs considerably, the material and technological resources that contribute to their “functionality” have a shared substrate in plastic and copper, solvents and silicon. Electronics typically are composed of more than 1000 different materials, components that form part of a materials program that is far-reaching and spans from microchip to electronic systems. (…) to produce a two-gram memory microchip, 1.3 kilograms of fossil fuels and materials are required.

(Jennifer Gabrys, Digital Rubbish. A Natural History of Electronics, Ann Arbor 2011)

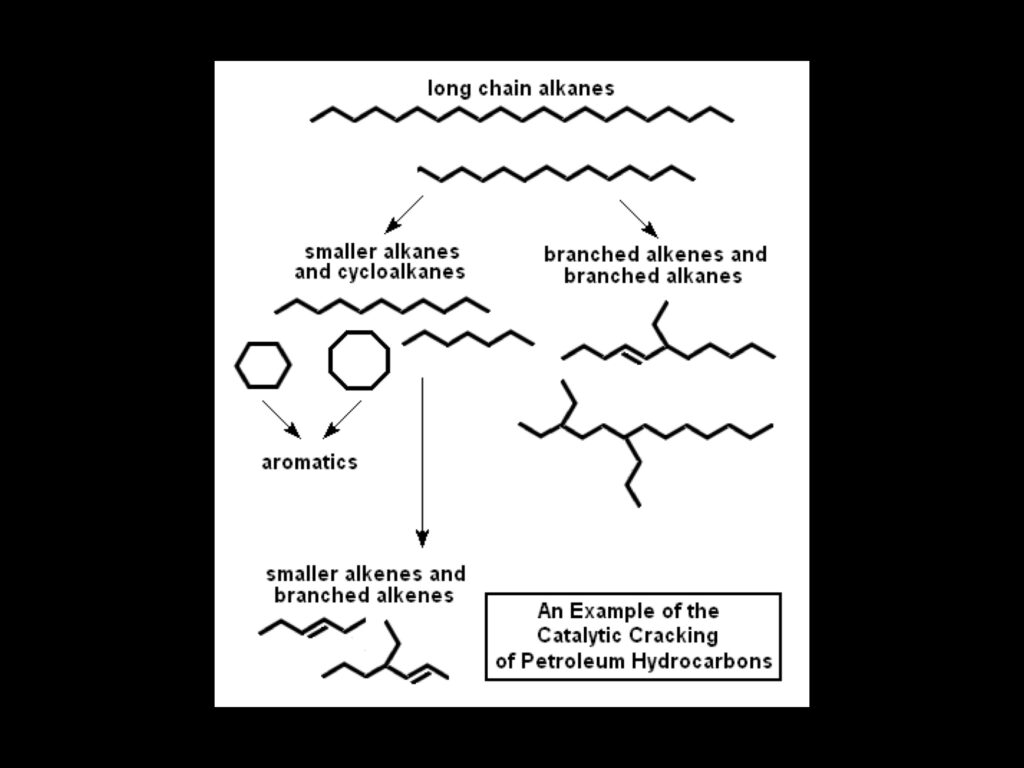

Cracking paradigm

The operational approach of informatics—to convey and calculate everything through discrete symbols —equals the operational approach of industrial chemistry—to rip complex materials in their smallest parts, molecules and atoms, and to recombine and optimize them.

Elements become isolated, analyzed, synthesized, and enter into circulation as deterritorialized bits of information that can be traded in complex, global ways. From soil to minerals to chemicals, their scientific framing and engineering is also a prelude to their status as commodities. (…) The periodic table is one of the most important reference points in the history of technological capitalism. The insides of computers are folded with their outsides in material ways; the abstract topologies of information are entwined with geophysical realities.

(Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media, Minneapolis 2015)

Digital Culture keeps unfullfilled petromodern promises

Understood in this expanded sense, extraction involves not only the appropriation and expropriation of natural resources but also, and in ever more pronounced ways, processes that cut through patterns of human cooperation and social activity. The prospecting logics (…) in the case of literal extraction take on peculiar characteristics here – since they refer precisely to forms of human cooperation and social activity.

(Sandro Mezzadra/Brett Neilson, »On the multiple frontiers of extraction: excavating contemporary capitalism«, Cultural Studies 2-3, 2017)