Two panels co-chaired by Alexander Klose and Benjamin Steininger within Petrocultures 2026 Dresden: »Situating Energy«, August 26-28, 2026

Please share and send proposals until January 18 2026!

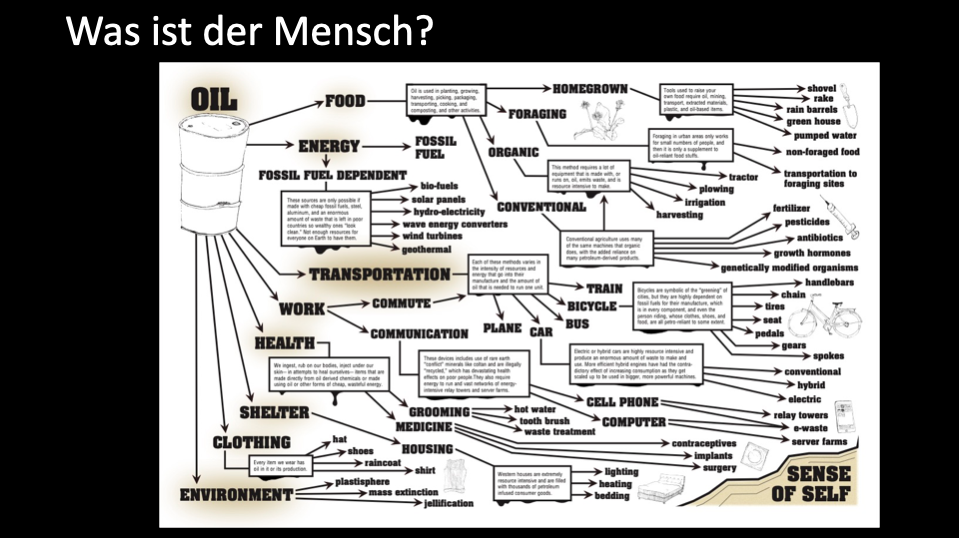

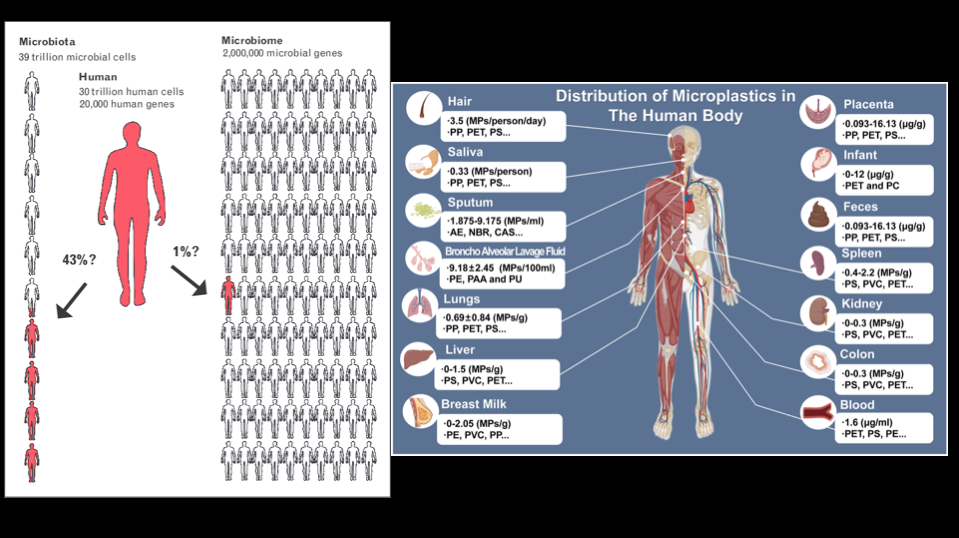

The plethora of new materials in the petromodern era—refined fuels, ammunition, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, plastics—were fashioned as complex chemical-industrial products. Current proposals for an ecological and just transition moving away from fossil resources and other destructive forms of extractivism largely rest on the ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ transformation of exactly these petromodern developments in chemical sciences and technology. However, despite its pivotal historical role in shaping the petromodern present, chemical technology has received little attention in petromodernity research.

With our panels we propose to read the programmatic Dresden call for “Situating energies” as a motivation to focus on the chemical sciences, technologies and infrastructures that provide energy and materials for all types of societal metabolisms— and on their social and cultural repercussions. In doing so, we investigate both the epistemologies behind chemical principles and technologies, as well as their geographical and historical situatedness—in our case in Central Europe, in Germany, in the former GDR, at the crossroads of historical experiences with different types of petromodernity: capitalist, NS, social-democratic, socialist, and post-Soviet.

The aim of our panel is to identify and analyze chemical-societal “double bonds” that combine perspectives on chemical technologies with perspectives on social, societal and political experiences. We therefore invite proposals to address chemical geographies and constellations from industry and scientific research to social and cultural aspects; from chemical factories and laboratories to bodies and landscapes. We encourage contributions from all fields of social and cultural research, as well as from chemistry, the humanities, history, and artistic or curatorial research. Although our focus is on Central Europe, we welcome contributions that deal with chemical geographies around the globe.

…