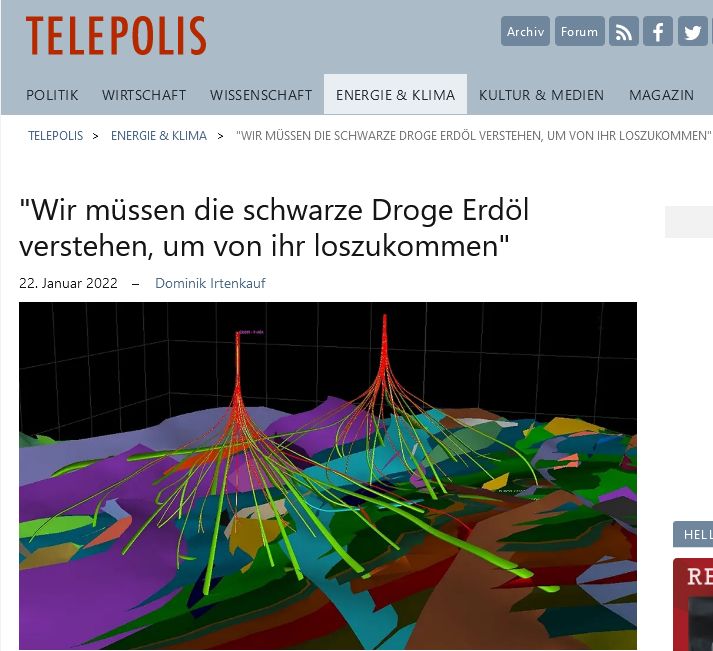

Alexander Klose at the University of Possibilities in Lützerath

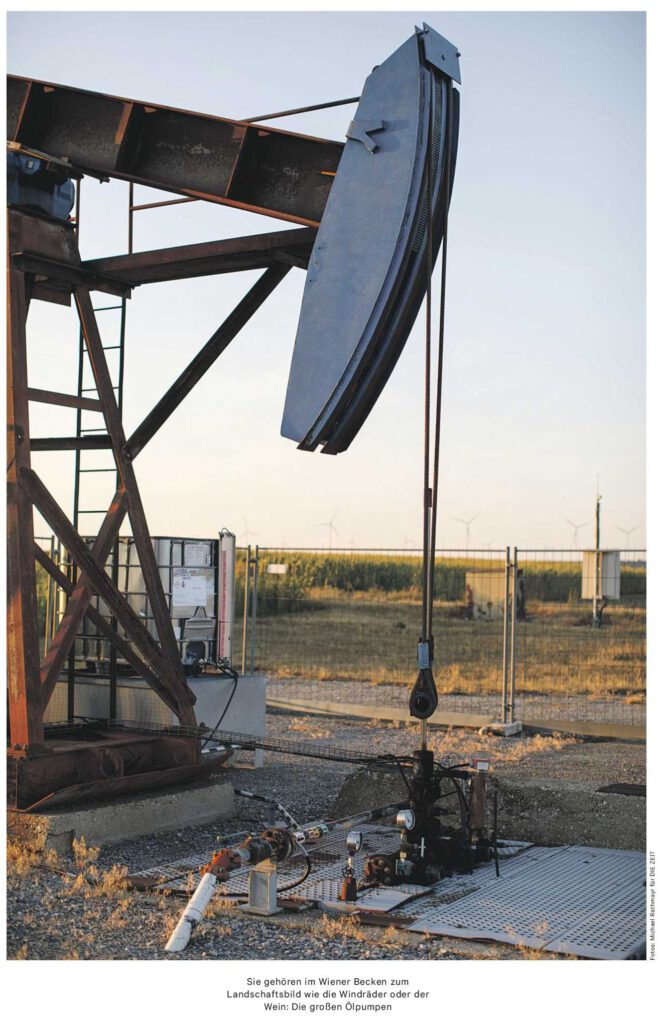

Lützerath is a village in the western Rhineland that had to make place for one of Germany’s most contested fossil fuel projects. Since the 1980’s citizens, politicians and NGOs like BUND have been fighting against the plans of North Rhine-Westfalia’s energy giant RWE to double the size of a hundred year old brown coal mine in order to take out a couple of hundred million tons of brown coal. Dozens of law suits, government changes, parliament hearings, demonstrations, climate agreements, climate catastrophes (the Erft valley area that was so heavily flooded in the summer of 2021 is right around the corner), occupations and evictions later, the situation has still not been settled.

A temporary stop has been put to the enlargement plans, but not all of the territory and the villages on it, destined to be destroyed according to the initial plans of RWE and the then social-democratic government of North Rhine-Westfalia are secured. Despite the political decision to completely end the use of coal as energy source in Germany until 2038, or even 2030. In 2015, Ende Gelände startet its direct actions of civil disobedience against coal extraction and combustion with blockades in the Garzweiler mines. Human ecologist and climate activist Andreas Malm mentions them a couple of times in his book How to blow up a pipeline, a plea for direct militant actions like blockades and sabotage to flank the peaceful mass protests of Fridays for Future and the like in order to enhance their assertiveness.

Lützerath has become a hotspot for the struggle when one of its old citizens refused to sell his house and stayed while RWE started to demolish houses and tear out streets and infrastructure around in January 2021, inviting activists to stay with him. In Sept 2022 this last man standing left after having finally lost his law trials against eviction in March. Since then the camp has been officially turned into an illegal squat, and the squatters have proclaimed the ZAD Rheinland in Lützerath, following the example of the militant Zone à défendre (zone to be defended) in France, The Netherlands, and Switzerland.

I had been invited to talk about our work with Beauty of Oil in the framework of a “University of possibilities”, a series of workshops, presentations and experimental discourse formats intended to accompany and maybe even ground activism with philosophical and speculative thought. “Philosophy can also be direct action,” as Lee, one of the initiators who had invited me, told me in the evening when she toured me around camp after my talk.

Here’s the abstract of my talk:

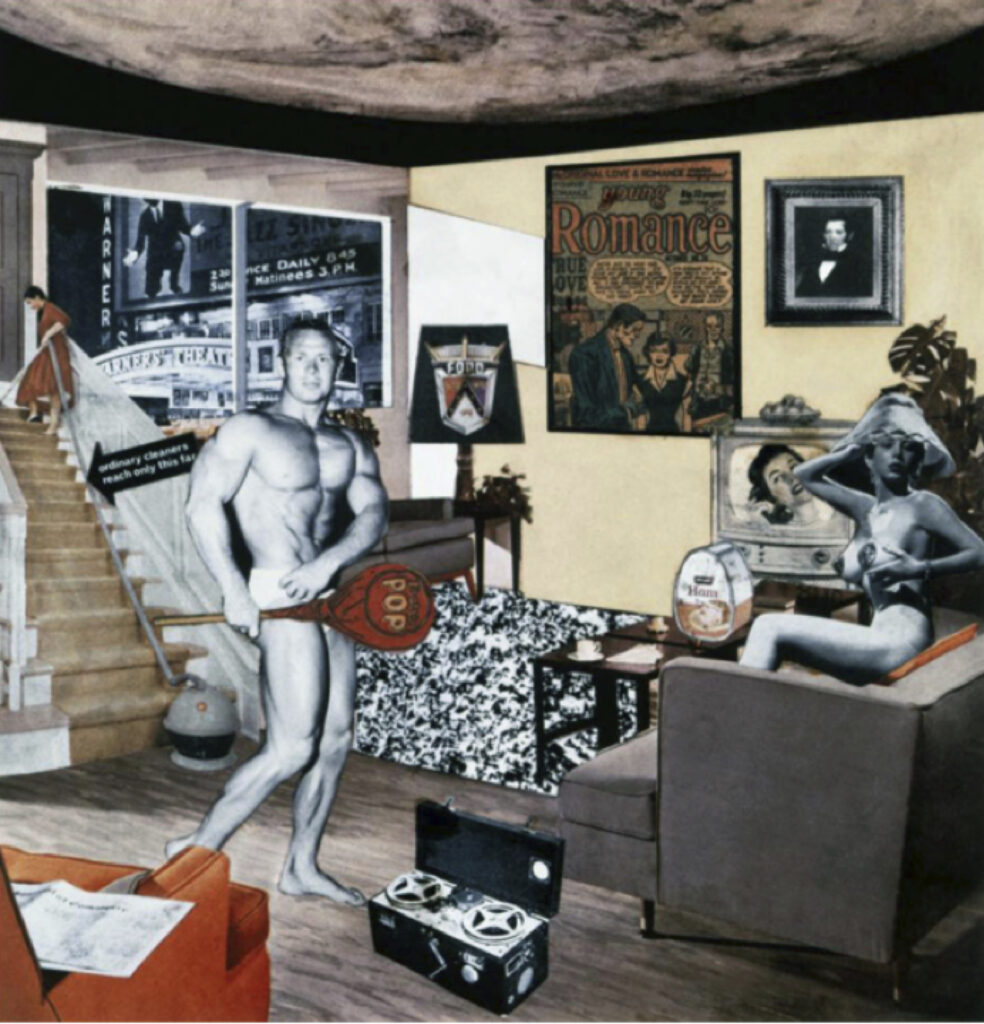

Just What is It That Makes Today’s Lifes So Different, so Appealing? – on the tenacity of petromodern claims and ways.

Presentation and discussion by/with Alexander Klose

(Research collective Beauty of Oil, Berlin/Vienna; Office for precarious concepts and undisciplinary research, Berlin)

Living in the plastic world / Living in the plastic world / Plastics, plastics everywhere / Where I walk and stand / PVC, PVC everywhere.

This is how A+P, an early German Punkband, put it in 1980.

Artificial matter, artificial fertilizer / Artificial grass / Artificial life / False teeth, false eyelashes / False love / All false here.

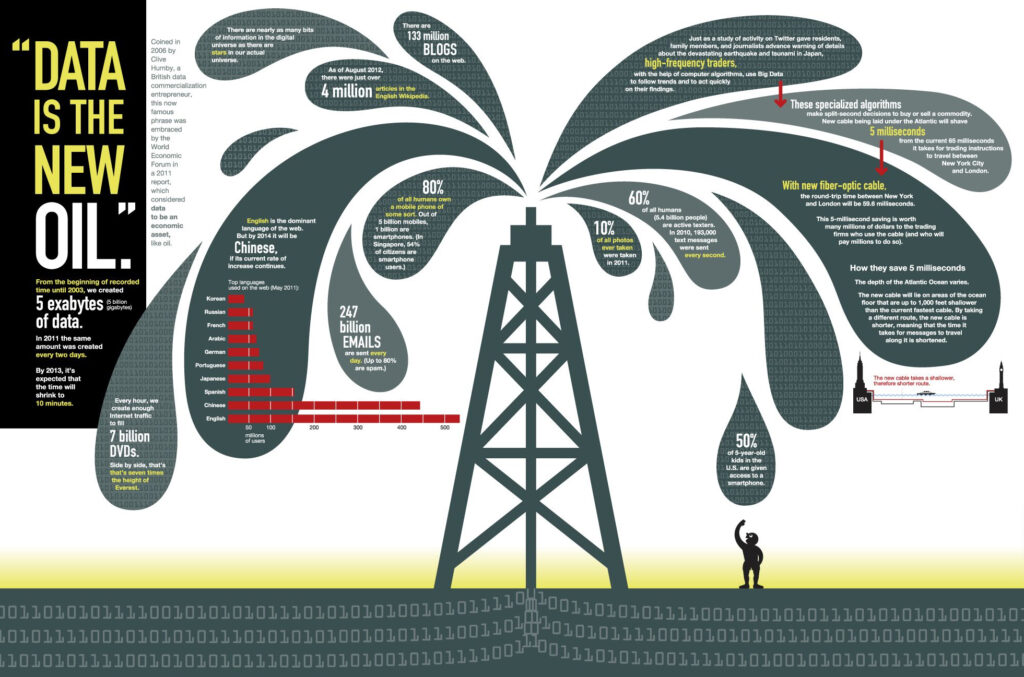

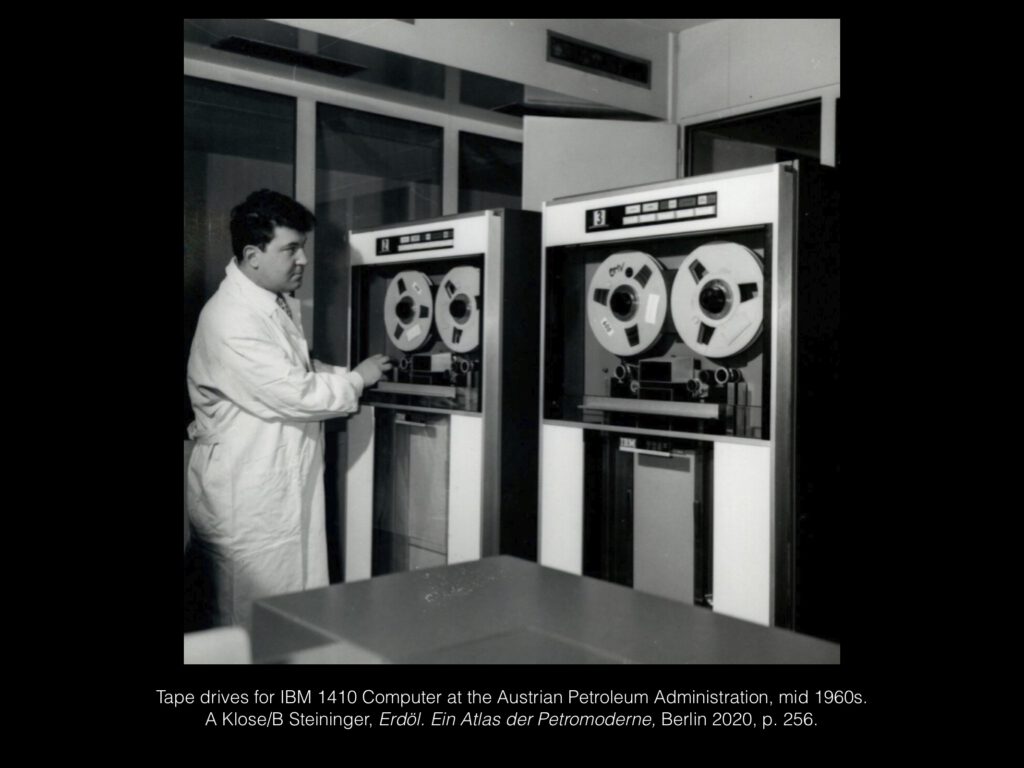

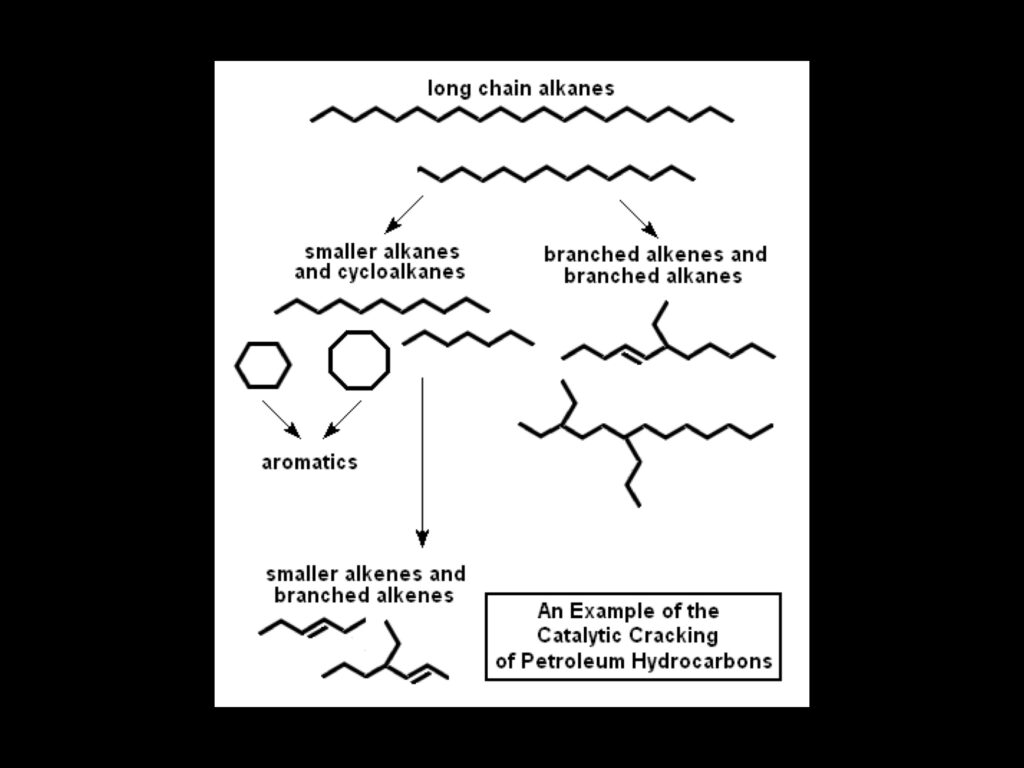

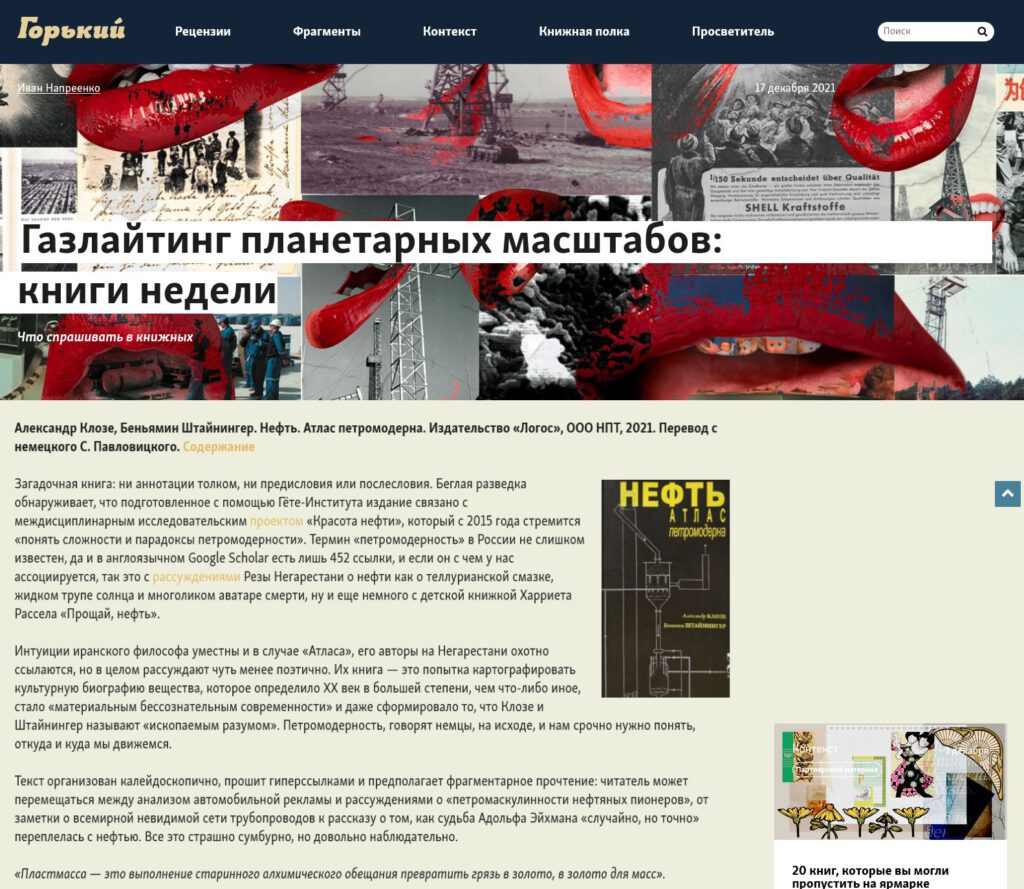

We have been living in petromodernity—the era of petrochemically based fuels and materials saturating all regions of life—for more than 100 years. Plastics is the new prima materia of this age, embodiment and incarnation of a second nature. For more than 50 years, people around the globe, but especially in the north-western heartlands of the petromodern civilization process have gotten increasingly aware that some things are fundamentally wrong with this time and its ruling principles. Starting in the late 1960s, the emissions of factories and cars transmuted from a sign of progress into one of imminent dangers, and plastics from the most modern material and guarantor of luxury for all into a cypher for everything that was a lie in the modern promises.

Yet, the dynamics of petromodern and—in a larger picture—fossil economics, claims, life styles, and belief systems haven’t been decelerated. Quite the opposite: the Great Acceleration has been continuing more or less full force, with the amount of consumer goods, cars, transport, energy use, plastification, extraction, and toxic emissions increasing globally against all objections or better knowledge.

Why is that so? And how can it be overcome?

The research collective Beauty of Oil works on understanding these petromodern dynamics in their tenaciousness. My talk introduces our projects, core theorems and approaches, and discusses possible future perspectives between technological fixes, ecological socio-economic reform and radical revolution.